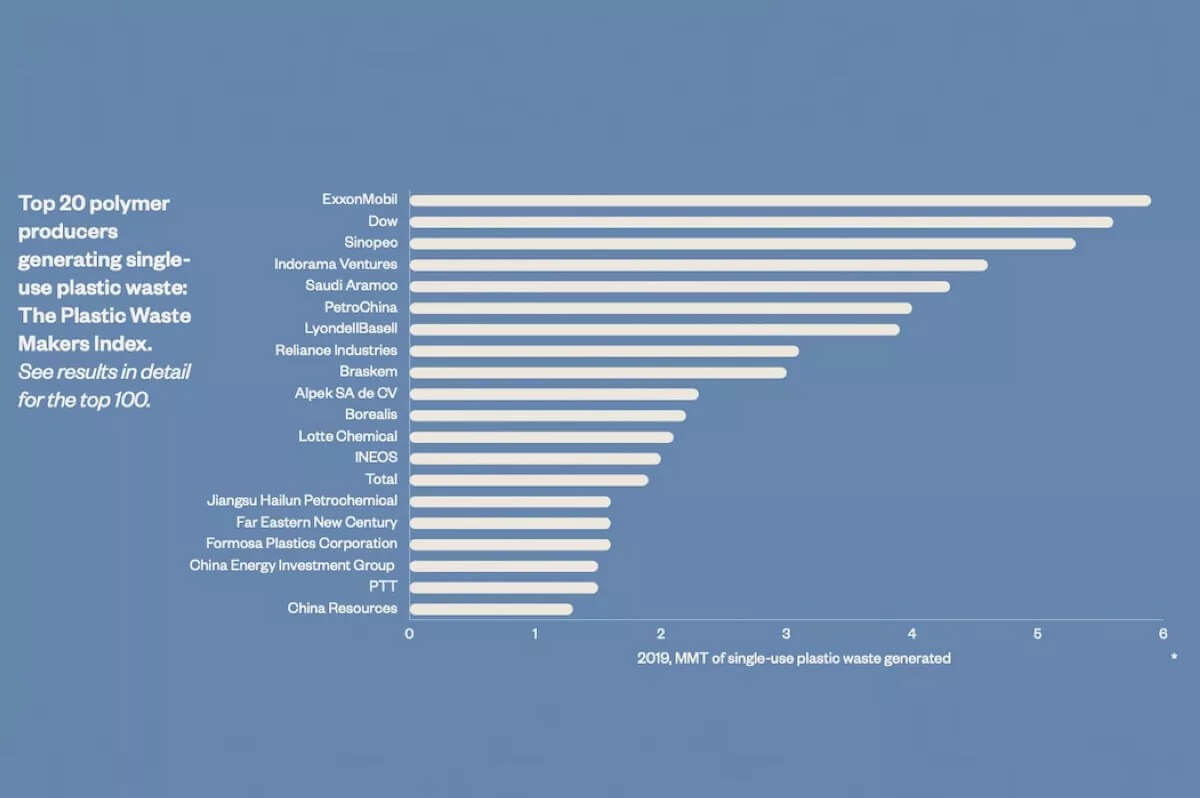

20 Companies Produce More Than 50% of the World's Single-Use Plastic Waste

A new report reveals that a small group of petrochemical companies are fueling the global plastic crisis. These major producers drive demand for single-use plastics, despite growing public pressure and environmental consequences.

While a lot of plastic waste activism has focused on the choices we make as consumers, those choices are inherently limited by the products made available to us. Now, a first-of-its-kind research project from Australia’s Minderoo Foundation has traced the problem to its source.

“The key findings of the Plastic Waste Makers Index are that just 20 companies are responsible for more than half of all the single-use plastic waste generated in any year and a similar number of global banks and investors are funding them,” Dominic Charles, the director of finance and transparency for the Minderoo Foundation’s No Plastic Waste division, said in a pre-recorded interview shared with reporters.

Who’s to Blame?

The Plastic Waste Maker’s Index set out to determine who is really responsible for the single-use plastics that form the bulk of all the plastic waste that is either burned, landfilled, or leaked into the environment every year. To do this, the Minderoo foundation spent a year working with a team of experts from research hubs like Wood Mackenzie, the London School of Economics, and the Stockholm Environment Institute.

Previous research efforts have focused on the companies behind plastic packaging. For example, Break Free From Plastic’s annual brand audit counts which companies’ labels show up most frequently on plastic trash items collected around the world. Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Nestlé have “won” the top three spots since the audits began in 2018.

The Minderoo Foundation, however, took a different approach by determining for the first time which companies actually made the plastic polymers that shape Coca-Cola bottles and other forms of plastic waste.

“The Plastic Waste Makers Index is a research effort that, for the first time, establishes a connection between the petrochemical companies at the very start of the plastic supply chain, and the plastic waste that is generated at the end,” Charles explained.

The report found 20 of these companies are responsible for more than half of all plastic waste, and 100 of them are responsible for 90% of single-use plastic production.1 ExxonMobil is the leading culprit, producing 5.9 million tonnes of the stuff in 2019. In second place comes U.S.-based Dow, with China’s Sinopec taking third. Indorama Ventures and Saudi Aramco round out the top five.

The study didn’t just look at who makes the plastic, but also who funds it. It found that nearly 60% of the commercial finance making single-use plastic production possible comes from just 20 banks, with Barclays, HSBC, Bank of America, Citigroup, and JP Morgan Chase in the lead. Together, the 20 banks have loaned a total of $30 billion to the sector since 2011.

The study further found that 20 asset managers own more than $300 billion worth of shares in the companies behind petrochemical polymers and $10 billion of this goes directly to making those polymers. The top five asset managers with shares in these companies are Vanguard Group, BlackRock, Capital Group, State Street, and Fidelity Management & Research.

Focusing on those responsible for the problem also enabled the report authors to better understand its scope. For one thing, it shows we are currently very far from a circular economy that would see plastic material reused rather than discarded. The top-100 polymer producers all largely use “virgin” fossil-fuel-based material to make their plastics, and recycled plastics only accounted for no more than 2% of the total produced in 2019.

What’s more, the situation looks to get worse without action. Capacity for virgin, fossil-fuel-based plastic production could jump 30% in the next five years, and as much as 400% for some companies.

Intervention in the form of regulation could change this, of course, but currently many governments are heavily invested in the production of new plastic polymers. In fact, around 30% of the sector is state-owned, with Saudia Arabia, China, and the United Arab Emirates in the lead in terms of how much they own.

What Can be Done?

The report's authors hope the information they provide will be used to work for a better outcome.

“Tracing the root causes of the plastic waste crisis empowers us to help solve it,” former U.S. Vice President and environmental advocate Al Gore, who wrote the foreword to the report, said in a press release. “The trajectories of the climate crisis and the plastic waste crisis are strikingly similar and increasingly intertwined. As awareness of the toll of plastic pollution has grown, the petrochemical industry has told us it’s our own fault and has directed attention toward behavior change from end-users of these products, rather than addressing the problem at its source.”

In order to address that problem at its source, the Minderoo Foundation made the following recommendations:

- Polymer-producing companies should be required both to disclose internal data about how much waste they generate and to move towards a circular model, making recycled instead of virgin plastics.

- Banks and other financial institutions should move their money away from companies making new plastics from fossil fuels and towards companies following a circular model.

Part of this response means paying attention so that attempts to solve the climate crisis don’t end up worsening the plastic problem. As report contributor Sam Fankhauser—Oxford University Professor of Climate Economics and Policy and former director of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change at the London School of Economics—put it in a pre-recorded interview, some of the “cast of characters” behind the two crises are the same.

“The people who produce carbon emissions, the petroleum industry, a lot of the same companies are also in the plastic industry,” he explained. “There’s a worry that as their returns get squeezed on the refined product side, they’ll move into plastic, so, reducing the climate change problem, but increasing the plastic problem at the same time.”

However, Fankhauser added the fight against plastic pollution can learn a lot from the climate movement. Specifically, forcing companies to be transparent about the way they contribute to the problem is the first step to getting them to take responsibility for it.

“The behavior towards carbon emissions changed once firms were forced to measure, to manage, to report their carbon emissions and something very similar can and should happen with plastic,” he said.

The report’s emphasis on corporate responsibility doesn’t mean we shouldn’t care about how much single-use plastic we use and work to reduce that use when we can, Charles said. But it does mean we should be honest about what is and is not within our power as consumers.

“We as individuals have a responsibility to manage our own consumption,” he said. “But we’re not going to make meaningful progress to eliminate plastic pollution until the companies in control of the tap, the fossil fuel plastic production, start making plastics out of the waste we’ve already created.”