If you’ve ever traveled by car in Mexico City, there’s a chance part of those travels involved the Anillo Periférico, a congestion-plagued beltway that fully encircles the center of one of the most polluted cities in the world.

Not to be confused with the city’s inner ring road, the Circuito Interior, Anillo Periférico is famous for elevated sections (a relatively new addition) propped up by hulking concrete pillars that collectively form a sort of loopy fence around the heart of Mexico City. In a city with already dizzying roadways, the Periférico is particularly dramatic in that it encases the city, which has long struggled with dangerously poor air quality, within a ring of smog.

It would seem that an iconic motorway encircling a city with bumper-to-bumper traffic and off-the-charts bad air would be the ideal place to launch an initiative that pairs smog mitigation with beautification — something to improve air quality and somehow make a winding mass of concrete highway infrastructure more aesthetically appealing.

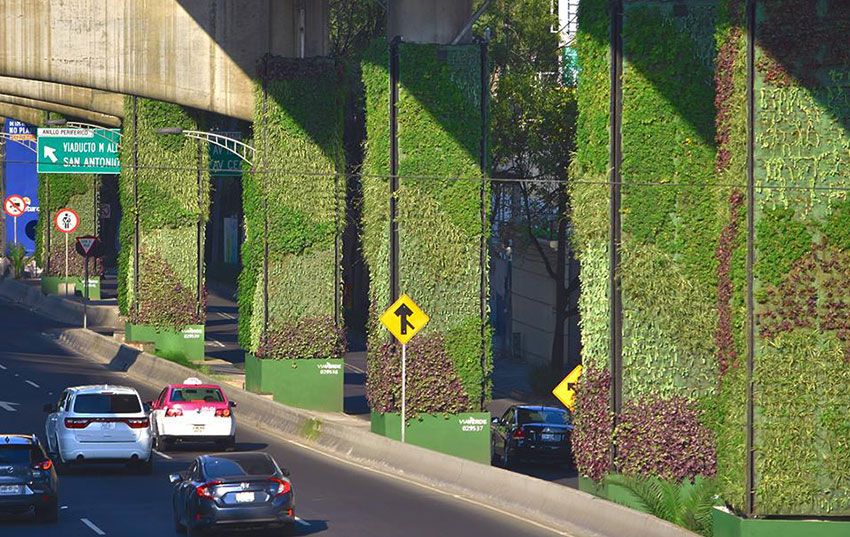

In 2016, such an initiative was hatched in the form of Via Verde, a project that’s seen around 1,000 of the Periférico’s unsightly columns be transformed into lush vertical gardens that lend the street-level section of the highway a “World Without Us” vibe — like Mother Nature has finally come to reclaim Mexico City, starting at the root by taking back one of the city’s most notorious modern day ills: its roads.

The plant-bedecked pillars are a surprising and beautiful sight. Via Verde demonstrates how easily concealing ordinary highway columns beneath greenery can transform a lamentable space for the better and make driving along it, well, a bit more pleasant. And, in this instance, it can also ostensibly lower air pollution levels.

Or maybe not.

As reported by the Guardian, Via Verde has been under fire as of late for being a cosmetic job — that is, it serves no greater purpose than just making parts of Anillo Periférico look pleasing to those who are stuck on it. (Per the TomTom Traffic Index, traffic congestion in Mexico City tops all other global cities.)

There’s nothing wrong, of course, with looking nice, especially when it involves high-traffic road infrastructure in a city of over 20 million residents. Critics of Via Verde, however, claim that the smog-absorbing qualities of the vertical gardens that were promised are, in reality, nil. What’s more, Via Verde has been accused of indirectly promoting car ownership during a time when so many groups in the city are pushing for residents to drive less. Critics believe the project rewards motorists — here’s something pretty to look at as you contribute to worsening the city’s air quality — instead of subtly discouraging them from driving.

“The idea of turning a grey city green feels good to its inhabitants. But in reality it’s just aesthetics. At the end of the day, it’s not going to change the city,” says Sergio Andrade Ochoa, public health coordinator for non-governmental pedestrian advocacy group Liga Peatonal.

Beautiful to look at but boasting ‘negligible’ environmental benefits

There were high hopes when architect Fernando Ortiz Monasterio of landscape design firm Verde Vertical first put feelers out to see how residents felt about a project that camouflages road infrastructure with a prefab paneled framework of succulents.

Monasterio’s March 2016 Change.org petition speaks of a project that would “produce enough oxygen for more than 25,000 residents, filter more than 27,000 tonnes of harmful gas yearly, capture more than 5,000kg of dust, and process more than 10,000kg of heavy metals.” Via Verde also claims to damper noise pollution and help reduce the urban heat island effect.

Impressive! To his credit, Monasterio’s vertical garden scheme was granted government approval, secured private funding and launched later that year. The process behind the initiative — from manufacturing to installation to upkeep — was streamlined, efficient and created local jobs. It’s also inspired other cities grappling with high levels of air pollution to consider similar solutions. And today, as mentioned, around 1,000 concrete columns — over 430,000 square feet in total — are a lot less hideous than they used to be.

But the plant themselves aren’t doing much. At all.

As the Guardian details, the “thriving” plants used in the concrete-concealing gardens, which feature innovative rainwater-fed drip irrigation systems, are hardy and lush. But they’re not capable of performing the kind of air-scrubbing heavy lifting touted by Monasterio in his 2016 petition. The current Verde Vertical website, while informative, only offers a minimal mention of the gardens’ air-cleaning qualities, which Monasterio now says are “negligible.”

Writes the Guardian:

While plants are crucial for combating climate change, using plants to mitigate air pollution through the process of phytoremediation — changing carbon into oxygen — is more complex. Only a few species have the capacity to purify the air in the way that the Via Verde petition indicated, and the succulents and other plants Verde Vertical favours for their low maintenance needs are not among them.

Roberto Remes of Mexico City’s public space authority, Autoridad del Espacio Público, admits that it was “never the intention” of Via Verde to help limit local emissions.

This not-so-small detail has irked groups like Liga Peatonal, which has claimed that greening one highway column costs the same as planting 300 trees, which in addition to cleaning the air, are effective at filtering stormwater, providing shade, lowering temps, elevating moods and, yes, adding all-important aesthetic oomph.

“In Mexico City, almost all of our local pollution and mobility problems can be attributed to the excessive use of private cars,” Ochoa of Liga Peatonal says. “We could just plant trees, but there’s a political fear of limiting the space in the city that is currently devoted to cars.”

As urban development news website UrbanizeHub points out, the citizen-driven greening project was originally pitched as one that repurposes infrastructure to create new public space. In reality, most would argue that Anillo Periférico, even with its fancy new green columns, doesn’t qualify as public space. There are no benefits to pedestrians or bicyclists and it “does not engage or empower citizens and it does not stop car use” writes UrbanizeHub.

How potent are vertical gardens and ‘forests?’

The debate over Via Verde initiative is reminiscent of the criticism lobbed at the garden skyscraper trend, a trend largely popularized by visionary Italian architect Stefano Boeri and his tree-covered twin residential towers, Bosco Verticale, in Milan. Inspired by that award-winning project, a slew of proposed residential high-rises with miniature balcony-forests incorporated into their respective designs are now slated for development in several European and Asian cities. (Paris, in particular, seems especially keen on shrouding its new towers with trees and shrubs). Some are designed by Boeri, some are not.

In a great piece for The Independent, Matthew Ponsford takes a deep dive into plant-clad high-rises — often dubbed as “vertical forests” — and the accusations of greenwashing against them.

He writes:

With only the Bosco Verticale to look to as a working protoype in Europe, plus other tree-trimmed structures taking shape far away in China, there is little solid evidence that garden skyscrapers will bring the benefits of cleaner air and greater biodiversity to a city like Paris, especially where trees are being lost or overshadowed to build them.

Much like the greenery-swathed towers that have emerged from the garden skyscraper trend, Mexico City’s Via Verde project sounds great on paper and, in its early stages, looked fantastic in renderings. But critics of the project have been clear: good looks — and intentions — just aren’t enough when you’re dealing with a smog-choked, congestion-riddled megacity like Mexico City. Greenery needs to pack a punch and serve a greater public purpose aside from aesthetics.

And it’s not that Via Verde is done wrong, it’s that the location — tucked away under an elevated beltway — isn’t the most ideal. It would be great to see Monasterio and other urban greenery specialists take on similar large-scale projects in areas that are defined by pedestrian movement, not standstill vehicular traffic. Or, better yet — and this is what groups like Liga Peatonal are getting at — use those same resources and that same passion to develop tree-studded horizontal gardens that are perhaps better equipped to handle the city’s stifling air.