One hundred years ago, Rowland Caldwell Harris was the visionary commissioner of works for Toronto—sort of a nicer, Canadian version of New York’s Robert Moses. John Lorinc writes for The Globe and Mail that Harris “left his civic fingerprints all over Toronto, building hundreds of kilometers of sidewalks, sewers, paved roads, streetcar tracks, public baths and washrooms, landmark bridges and even the precursor plans to the commuter rail network.”

When Harris built the Prince Edward Viaduct over a deep river valley, he built a lower deck to accommodate a future subway 50 years before it was needed. He also made the bridge far wider than it needed to be at the time, to accommodate a streetcar line down the middle as well as four lanes of traffic.

The streetcar line is gone and the sidewalks were narrowed, so it is now a five-lane car sewer with scary bike lanes. It has become “a straight, unencumbered raceway that seemed to naturally encourage drivers to accelerate once upon it.” The bridge had earned notoriety in North America for suicide, second only to San Francisco, California’s Golden Gate Bridge, until a 16-foot high barrier—the “Luminous Veil” designed by Dereck Revington—was installed in 2003. It has been successful at reducing deaths by suicide but now makes you feel like you are in a cage.

Meanwhile, the streets leading to it from either side have been modified for bike lanes and patios during the pandemic, and are now one lane in each direction.

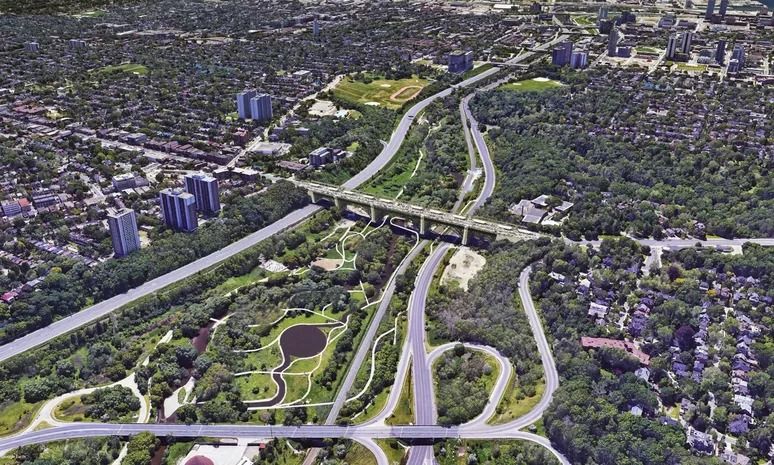

Architect Tye Farrow sees this as a great opportunity. The car sewer spans the Don Valley and the Don River, which over the years had been channelized and turned into a literal sewer. The Valley was destroyed by a multilane highway in the ’60s, by the railways before that, and was an industrial wasteland. Farrow wants to change all that, telling Treehugger that he wants to turn “the historic Bloor Street viaduct into a community space which amongst other things, offers a unique post-covid pedestrian experience in the city.”

Farrow says:

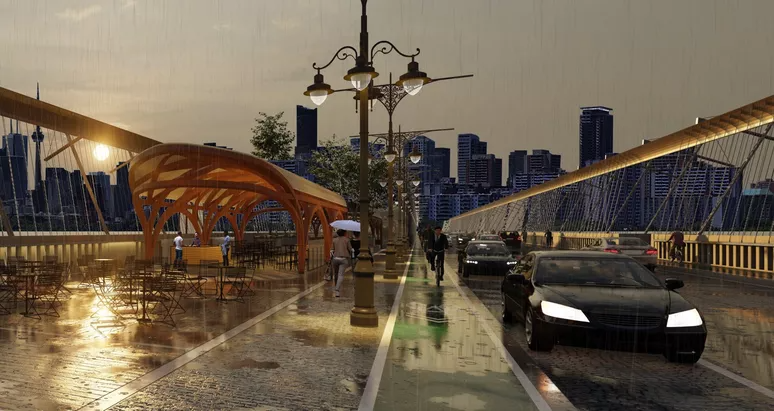

“While Bloor Street and the Danforth [the two streets leading up to the viaduct] for the most part are two lanes of traffic, the viaduct is five lanes wide; an opportunity to expand the public realm in a meaningful way at a remarkable place in the city. An important piece of the plan is also connecting the viaduct surface – Bloor St and the Danforth – to what has developed as a new ‘Brick-Bridge Park Precinct’ which is bookend and connected to the Viaduct to the south and the Brickworks to the north as one interconnected enhanced urban ecological natural park.”

In recent years, the Valley has been significantly improved, with public facilities like the Brickworks replacing industrial ones, and new cycling and hiking paths being introduced. It’s actually nice down there, so making that connection between the top and the bottom becomes very attractive. It is described as “an added jewel to the Lower Don Trail system, featuring enhanced trails, active and passive park activities, framed by a new direct connection to the Evergreen Brickworks to the north, and a new connection from the viaduct deck surface to the trail system below, allowing ease of access by Torontonians from Bloor and Danforth to the new park and Brickworks beyond.”

“The Market Bridge at the Prince Edward Viaduct can become a place where residents of Toronto could go regularly to experience the new creative food and retail ideas the city has to offer, with a social cause and mission; ever-evolving and changing. A place to come together and to share; a place that bridges and connects people from different backgrounds, cultures and ages. A place that causes health.”

Farrow knows about health, being a specialist in hospitals, and he also is a pioneer in mass timber, so it is logical that he would use wood for these pavilions and get down to the details of how it all goes together, with a “wood glue laminate roof structure and a ‘CLT-like’ all timber block wall; a no glue, no nail, curved wall made of small pine ‘sticks’” covered with a lightweight translucent membrane roof.

It is a grand vision, and what is happening below the bridge is as important as what’s happening above, with the Brick-Bridge park tying them together.

The Prince Edward Viaduct is a cultural touchstone in Toronto—a key player in Michael Ondaatje’s 1987 novel, “In the Skin of a Lion,” designed and built with care. But it and the highway under have become wastelands devoted to cars. It’s time to take back the street, or at least a portion of it. Farrow writes:

“The pandemic has offered a rare opportunity to envisage a more refined balance between transportation needs, the public realm, flexible community space, thereby creating a more energetic and complete urban environment for the citizens of Toronto.”

Indeed, it is an idea whose time has come.

Can it be updated?

Many will say that this can’t be done, that all the lanes are needed to deal with the traffic volume, but Farrow just sent this photo of the bridge as at time of writing, with two lanes closed to provide room to repair the Luminous Veil barrier. Farrow tells Treehugger:

“The south side of the bridge has been closed to traffic and only 3 lanes on the north side, plus sidewalk and two bike lanes… same as our plans. Remarkable, and traffic flowing beautifully. The the whole feel of the bridge totally has changed. Totally. Now we just need to take it a step further.”

Some might argue that it’s also time to rip out that highway that runners and cyclists get to use for one morning a year and restore the Valley too, but that might be a bridge too far.