Kift, a co-living community that Colin O’Donnell is building out of Sprinter vans, which he describes as “a new way to live and work wherever you want without giving up relationships or the comforts of home.” However O’Donnell also has a vision for the future of cities based on the technologies that many believe are coming down the road shortly.

O’Donnell tells that autonomous electric vehicles and a mesh of 5G technologies will make it possible to build a vehicle designed specifically for living and moving. He sees it as a new way for humans to live, “a type of city that isn’t attached to land the way it has been in the past.”

“Soon the nation might be filled with rolling homes full of boomers autonomously moving from buffet restaurant to the doctor’s office to charging station to Arizona in the winter. I love this idea, going to bed in Buffalo and telling my home to take me to Chicago for a ballgame.”

O’Donnell sees the mobile units meeting up for temporary events like Burning Man, where cities appear almost instantly.

Communities could pop up in parking lots; I love this vision where the sandbox, swimming pool and even the lawn are on wheels.

I complained that a problem with his idea was the low density that comes from building all on one level, that he might have to think vertically, like The Stacks (pictured above) in “Ready Player One,” but O’Donnell reminded me that trailer parks are in fact really dense, because the units are small and are packed closely together. This is confirmed in Strong Towns:

“If you had 70% home plots/15% roads/15% shared amenities like parks and squares, 1000sf plots, and 2.5 people per household, that works out to population density of 46,000 people per square mile — with one or two story construction! At this level of density, compared to about 9,000/mile for the denser Los Angeles suburb, you could easily have a lot of neat commercial stuff (bars, restaurants, shops, schools, etc.) within walking distance.”

O’Donnell imagines that people might move around according to their interests, perhaps a surfing community one year or a musical one at another time; they even might settle down for a while in a child-friendly environment with a permanent connection between two units.

The beauty of the model is that you are not trapped by real estate; you can move if your job moves, if your interests change, or, for that matter, there is a pandemic. In a normal year, 350,000 Canadians pack up and move to Arizona or Florida for the winter; It’s easy to imagine huge cross-border Kift traffic. You might get a situation like this, where the lead Kift unit has all the technology, the motors and the batteries, and it can tow other modules, bedrooms, and other living spaces to its next base.

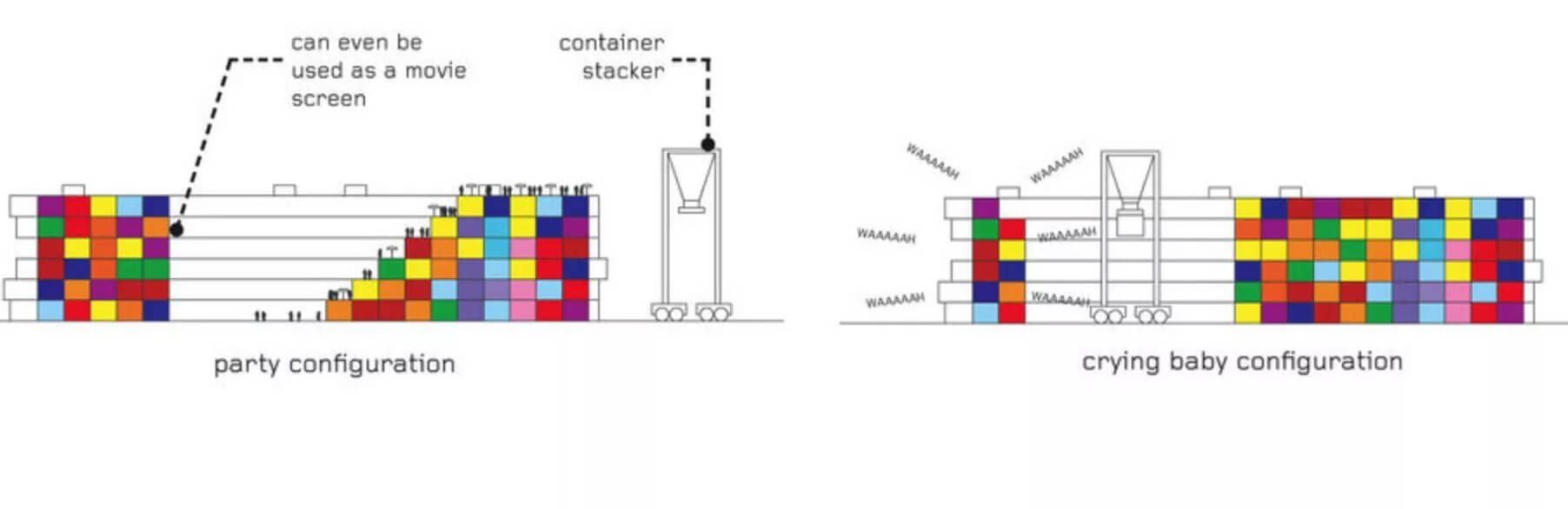

Needs change. Circumstances change. I always smiled at Andrew Maynard’s 2004 scheme of modular homes that could be rearranged on a whim from party configuration to crying baby configuration. Maynard talked about Le Corbusier’s idea that a house is a machine for living, writing “Like Corbusier, we love machines, but let’s not turn the house into the machine, rather let’s use the machine to erode social hierarchy and flatten real estate economics.” O’Donnell and Kift are doing exactly that, separating house from land, letting people pick their own social milieu, choosing where and how they want to live. It’s not about the box, but about the lifestyle.

Barbra Streisand sang Arlen and Mercer’s “Any place I hang my hat is home.” In the near future, it may be any place I park my Kift.