Floating Park in Rotterdam: How Recycled Plastic Is Transforming Urban Harbors (2025 Update)

Functioning mostly as a lushly planted offshore refuge for urban wildlife that's only partially accessible to people, Recycled Park stretches 1,500 square feet across a chain of interlinking hexagonal platforms constructed from recycled plastic and anchored to the harbor floor. Staggered at different heights, the platforms — buoyant garden beds, really — are planted with different types of vegetation geared to attract a range of critters including nesting aquatic birds. The whole beautiful spread is captured in the video below.

What's more, the undersides of the green "building blocks" that bob just below the surface are specifically designed to nourish aquatic life. As the foundation explains, the bottoms of the platforms have "a rough finishing where plants can have enough surface to grow and fish a place to leave their eggs." This, in turn, can help "upgrade the ecosystem of the harbor."

(The recycled plastic blocks, by the way, were developed by the foundation with input from students from several Dutch universities including TU Delft, Rotterdam University and Wageningen University.)

Also running through the quaint harborside park is a canal where, as the foundation explains, "birds and small fish can find shelter here and the space to grow before entering the deep waters."

A floating refuge for birds, bees and people

With floating greenery firmly covered, what about the park-y part of Recycled Park — the public space?

As mentioned, the project — a prototype at this point that could ultimately be improved and expanded — is mostly for the birds (and fish and insects and so on) as it predominately aims to "stimulate ecology in Rotterdam Harbor."

There are, however, two platforms that function exclusively as seating elements. Connected to the shoreline by gangplanks, these floating conversation pits, one on each end of the park, resemble oversized hexagonal hot tubs that have been drained of water. They look like pleasant places to sit back and relax out on the water, watching massive boats pass by amidst greenery that gently undulates with the waves of the harbor.

Unveiled on July 4, Recycled Park is currently floating in Rijnhaven, a quiet harbor basin on the south bank of the Nieuwe Maas, a distributary of the Rhine that flows through the heart of Rotterdam and into North Sea. Not too far from Recycled Park — also home to a striking tri-domed floating event pavilion and and a floating forest — is Rotterdam's iconic Erasmus Bridge.

This all being said, Recycled Park, flanked by glistening residential high-rises and amenities galore in a revitalized industrial area located smack dab in the middle of Europe's busiest port, is in the primo spot as far as waterfront Rotterdam real estate goes. (Easy access to public transit and water taxi doesn't hurt.)

In its current location, this singular park prototype will be seen — and get used.

Making good use of 'plastic soup'

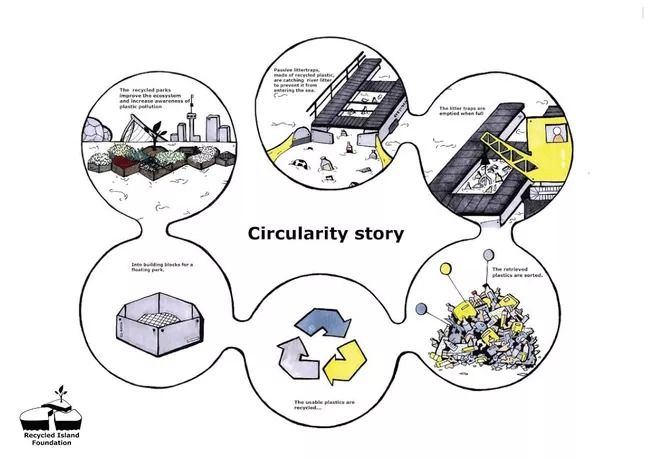

One might wonder exactly how much marine waste the Recycled Island Foundation retrieved from the Nieuwe Maas in order to fabricate the park's recycled plastic platforms all the while demonstrating that "recycled plastic from open waters is a valuable material and suitable for recycling?"

While the foundation doesn't give any exact number in terms of quantity, is does note that the "trapping process" in the harbor and river took roughly a year-and-a-half.

A press release (perhaps with a bit lost in translation) explains:

This resulted in a good working system, that works efficiently even with heavy ship traffic, tidal changes and different wind directions. The Litter Traps catch the plastics by using the existing stream of the river and keep the plastics inside even when the direction of the stream turns.

Architect Ramon Knoester, who founded the Recycled Island Foundation as a way to "find an active approach to worldwide plastic pollution in open waters," explains why drawing attention to the scourge of plastic polluting the world's oceans and waterways — aka "plastic soup" — is even more important that injecting a dash of greenery-studded oomph to the industrial Rotterdam waterfront:

The water is in many cities the lowest point, resulting in the unfortunate accumulation of litter in our rivers. When we retrieve the plastics directly in our cities and ports we actively prevent the further growth of the plastic soup in our seas and oceans. Rotterdam can set an example for port cities everywhere in the world. The realization of the building blocks in recycled plastics is an important step towards a litter free river.

In April, months before Knoester's recycled plastic floating garden debuted at Rijnhaven, he gave an interview to U.K.-based outdoor adventure news site Mpora while attending the Edinburgh International Science Festival.

He elaborates more on the ultimate aim of Recycled Park: "Hopefully people become aware that if you collect your plastics and hand them in, you can still make nice, new products with it," he says. "So hopefully one day we'll reach the point where people will say 'okay we'd like to have more floating parks and more floating structures, so we should be more careful with our plastic waste.'"

Rotterdam: The port city obsessed with a greener, cleaner future

Knoester hints to Mpora that he'd like to eventually trial the Recycled Park concept in other port cities like London and Antwerp, both cities that, similar to Rotterdam, straddle heavily trafficked tidal rivers that flow into the North Sea. And even if the work of the Recycled Island Foundation remains limited to Rotterdam for the near future, you really couldn't ask for a better place to launch a biodiversity-bolstering floating park-garden made from recycled plastic.

While quintessentially Dutch in disposition, the Netherlands' second-largest city is very un-Dutch when considering its vaguely Los Angeles-like urban landscape. Nearly leveled completely by bombing during World War II, Rotterdam was rebuilt in a wildly different manner than the city that came before it. The result is jarring, exciting and a bit schizophrenic. This is a city that has been glancing into — and embracing — the unconventional and the innovative ever since it was reborn in the 1950s.

Because of its gritty industrial history and its relentless drive to innovate, Rotterdam tends to attract fearless visionaries — entrepreneurs, engineers, urban planners, scientists, architects and on. As Fast Company detailed in a 2016 feature on the city's emergence as a global hotbed of sustainable urban design, Rotterdam is a city that "loves to play with new ideas."

In addition to mentioning a slew of more radical in-the-works projects like a floating dairy farm and a massive housing development that also doubles both as a wind turbine and an observation wheel, Fast Company chats with Daan Roosegaarde. Perhaps Rotterdam's most well-known sustainable designer, Roosegaarde has received significant international attention for his socially aware and sensorially dazzling creations, which include glow-in-the-dark bike paths and a sculptural 'smog vacuum cleaner.'

"Why not be in a city where you can test it, make a mistake, learn something?" he tells Fast Company of his adopted city. "It's a playground where you experiment, you show what works. Then you scale and go onwards."

So keep an eye out... you might just see a recycled plastic micro-park float into a port city near you.

🌱 2025 Update: Recycled Park’s Ongoing Impact and New Expansions

Since its debut, the Recycled Park in Rotterdam has continued to thrive as a beacon of sustainable urban innovation. In 2024, the Recycled Island Foundation expanded the project by adding new platforms, doubling the park’s total area. The park now supports an even wider variety of bird species, aquatic life, and native plants, contributing significantly to Rotterdam’s harbor biodiversity goals.

Moreover, the success of Recycled Park has inspired similar floating initiatives in cities like Antwerp and Hamburg, demonstrating the global potential of recycled plastic urban parks. The Foundation also reported that their litter traps have now collected over 50 tons of river waste, highlighting the project’s lasting environmental impact.

Looking ahead, the team plans to integrate solar panels into future platforms, combining renewable energy with green space. The Recycled Park remains a world-leading example of how creative design and sustainability can reshape the future of urban living.

Stay tuned for more updates as Rotterdam continues to lead the way in eco-friendly urban transformation!