Many cities in the United States could grow their own food locally, raising enough crops and livestock to meet the dietary needs of all residents. This is the finding of an interesting new modeling study from Tufts University, which analyzed the potential for local food production in 378 metropolitan areas across the United States and envisioned food production as a national closed-loop system.

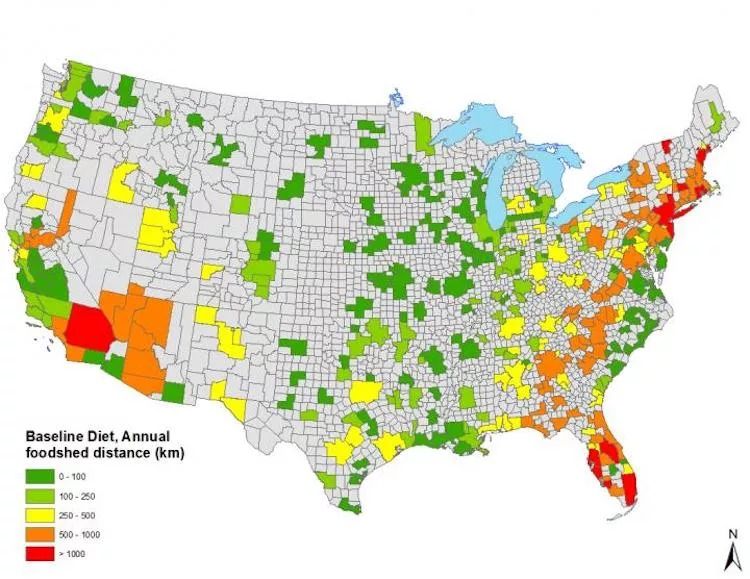

“Local” was defined by the researchers as being within 155 miles (250 kilometers) of a city, and the feasibility of producing food to support seven different diets – ranging from the meat-centric “typical American” diet to veganism – was analyzed.

The researchers found that cities in the Northwest and the interior of the U.S. had the greatest potential to raise their own food. Cities along the Eastern Seaboard and in the Southwest had the least potential and would not be able to meet all their own dietary needs, even if every acre of agricultural land was used for food production. This makes sense, as many of the cities are coastal and lack room for agricultural expansion.

Potential for local production increases as meat consumption goes down, to a point. When meat consumption was reduced to less than half the current average (estimated to be roughly five ounces per day), both omnivore and vegetarian diets had similar levels of localization potential. A press release from Tufts University quotes Julie Kurtz, one of the study authors:

“Imagine if we cut back to fewer than two and a half ounces per day by serving smaller portions of meat and replacing some meat-centric entrées with plant-based alternatives, like lentils, beans and nuts. More diverse sources of protein could open new possibilities for local food. Nutrition research tells us that there could be some health benefits, too.”

Each of the seven diet scenarios revealed the United States having a surplus of agricultural land for feeding the domestic population. Currently, some land is used to raise export crops and biofuels, but a focus on local food production would kickstart a conversation about how that land gets used. In the words of Christian Peters, lead author and associate professor at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts:

“It would be important to make sure policies for supporting local or regional food production benefit conservation and create opportunities for farmers to adopt more sustainable practices. Policies should also recognize the capacity of the natural resources in a given locale or region — and consider the supply chain, including capacity for food processing and storage.”

Although it’s a far cry from the current reality, it is a nice thought to imagine cities surrounded by fertile food production operations that transport freshly harvested ingredients to nearby homes, and then make use of the leftover food scraps as compost to fertilize fields and generate heat for greenhouses in a closed-loop system. It would require an enormous shift in the priorities of shoppers, retailers, farmers, and local governments, including a willingness to tailor one’s diet to the seasons (which could mean more coleslaw than Caesar salads in January). But at least this study shows what’s possible – and that’s the first step in effecting change.

This study does not take climate change into account; it’s based on current weather patterns. Nor does it analyze the cost efficiency of embracing more local food production. You can access the study here.