Does Shipping Container Architecture Make Sense?

Shipping container homes promise affordability, mobility, and sustainability—but is the hype justified? This article breaks down the benefits, challenges, and environmental realities of container-based architecture.

I grew up around shipping containers; my dad made them. I played with them in architecture school, designing a summer camp out of them, fascinated by the handling technology that made them cheap and easy to move. But in the real world I found them to be too small, too expensive, and too toxic.

Today, shipping container architecture is all the rage. Where containers were once expensive, now they are cheap and ubiquitous, and designers are doing amazing things with them. Did I make a terrible career move? Reading Brian Pagnotta in ArchDaily, in one of the most balanced and thoughtful articles I have seen on the subject of container architecture, I think perhaps not.

Pagnotta starts with the benefits:

There are copious benefits to the so-called shipping container architecture model. A few of these advantages include: strength, durability, availability, and cost. The abundance and relative cheapness (some sell for as little as $900) of these containers during the last decade comes from the deficit in manufactured goods coming from North America. These manufactured goods come to North America, from Asia and Europe, in containers that often have to be shipped back empty at a considerable expense. Therefore, new applications are sought for the used containers that have reached their final destination.

He then gives a bit of history, tracing container buildings back to a patent in 1989. Here, he is patently wrong; people were playing with them back in the seventies.

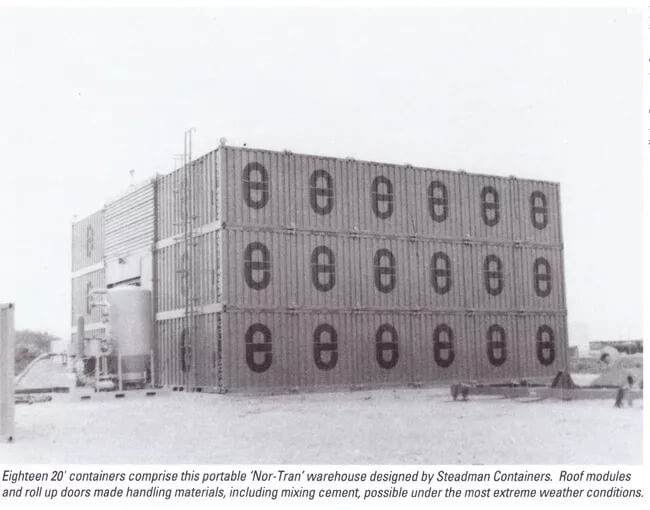

My dad built this in the seventies, moving shipping containers full of equipment to the Arctic, where he lined them up in two rows and put a roof between them and doors on the end, so that workers had an enclosed environment to unload the containers and assemble whatever it was. The key here was mobility; the next year when the containers were empty the building would be shipped south again. (A container cost $ 5,000 in 1970 dollars, you didn't just abandon it).

The same basic idea is being used by everyone from Adam Kalkin to Peter Demaria- they recognize that the container is too small an element for most functions, so they build between them.

When I played with shipping containers in the 70s at school, it was all about folding stuff out of them and about movement. The container was the box in which you shipped stuff. Because really, by the time you insulate and finish the interior, what are you going to do in seven feet and a few inches? You can't even fit a double bed in and walk around it. And you certainly couldn't live in any container made for international travel; to be allowed into Australia the wood floors had to be treated with seriously toxic insecticides. To last ten years in the salt air of a container ship, they were painted in industrial strength paints that are full of toxic chemicals.

The real attraction was their mobility. Who in their right mind would nail them down permanently?

At Archdaily, Peter picks up on all of these issues of toxicity and size. He also writes:

Reusing containers seems to be a low energy alternative, however, few people factor in the amount of energy required to make the box habitable. The entire structure needs to be sandblasted bare, floors need to be replaced, and openings need to be cut with a torch or fireman's saw. The average container eventually produces nearly a thousand pounds of hazardous waste before it can be used as a structure.

He concludes:

While there are certainly striking and innovative examples of architecture using cargo containers, it is typically not the best method of design and construction.

I have watched the shipping container meme with some bemusement and a bit of depression, thinking that I seriously missed the boat. But 30 years ago I thought them too small, toxic and expensive, and that hasn't changed. It is about to, as designers and builders finally figure out what shipping containers actually are, which is not just a box, but part of a global transportation system with a vast infrastructure of ships, trains, trucks and cranes that has driven the cost of shipping down to a fraction of what it used to be.

This is what I think is the future of shipping container architecture, and it is not a happy thought. Shipping containers have globalized the production of just about everything except housing, because houses are bigger than boxes.

When you think of a shipping container as more than just a box, but part of a system, then it begins to make sense. And the logical, and inevitable conclusion is that housing is no longer any different than any other product, but can be built anywhere in the world. The role of the shipping container in architecture will be to offshore the housing industry to China, just like every other. That is their real future.

If you care about getting consistent, high quality housing that's fast and cheap, this will make you happy. If you care about all those jobs that have vaporized in the housing crash, it's a problem, they've been exported.